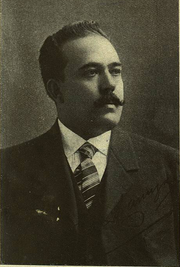

President Victoriano Consalus.

Victoriano Consalus was the ninth President of the United States of Mexico, serving from February 1914 to April 1920.

Presidential Election and the Hundred Day War

Consalus served as Secretary of State under President Anthony Flores. When Flores declined to run for a third term in 1914, the United Mexican Party nominated Consalus, who was well-known, flamboyant, and shrewd. Consalus was able to run on Flores' record of peace and prosperity, and in the 1914 Mexican elections he defeated the Liberty Party candidate, Senator Albert Ullman of California, by 11,702,470 votes to 7,521,428, winning majorities in every state but Arizona and Mexico del Norte.

In his inaugural address on 16 February 1914, Consalus promised "a better life for all our people," and in general limited his short speech to generalities. However, discussing foreign policy, he said, "Our land has had more than its share of war. Its history has been written in blood. From the days of the Conquistadores, to the North American Rebellion, through the Rocky Mountain War and the bloodshed of the Hermión dictatorship, we have suffered. We want no war, and so we prepare for combat sadly, hoping it will not fall to this generation to suffer the fate of its ancestors."

Consalus' words were motivated by the threat to the U.S.M. posed by French President Henri Fanchon. Fanchon believed he could make France a major power and establish French hegemony over South America by defeating the U.S.M. in war. Before the election, Flores had consulted with Consalus and Ullman on possible responses to the French chanllenge. Consalus thought the best response would be to order partial mobilization of the Mexican Army, station elements of the Pacific Fleet in the Caribbean and outside the Kinkaid Canal, and place guards in the large French quarter in Tampico. After winning election, Consalus presumably carried out these plans.

Consalus believed that a French attack on the U.S.M. would fail, and according to Sobel, relished the possibility of war, rejecting all attempts at mediation from other powers. When a French naval force held maneuvers in Argentinian waters, Consalus sent a note to President Lopez Vargas warning him of "dire consequences should the Argentine continue its warlike alliance with France." On 1 April 1914 Mexico broke diplomatic relations with Argentina, and three days later France recalled its ambassador to Mexico City. On 16 May French troops began arriving in Argentina "to assist that government in repressing guerrilla activities near the capital."

On 2 June a French brigade disembarked in Martinique. Ten days later, a major riot erupted in Tampico that lasted for four days. Fanchon sent the French fleet toward the port "to assist our countrymen in their fight against tyranny." The fleet arrived in the Caribbean on 22 June, and anchored in international waters just outside Tampico. When a second riot broke out on the night of 27 June, the French seized Tampico, beginning the Hundred Day War. During the next month, a second French force landed at the Kinkaid Canal, while a third was defeated by the Mexican Navy at the Battle of Campeche Bay and thus prevented from landing at Vera Cruz.

By 11 July Mexican and Guatemalan troops guarding the Kinkaid Canal had defeated the French marines there, forcing them to flee inland to the mountains. The French responded by reinforcing their army in Tampico on 15 July and launching a drive on Mexico City. The French troops freed any Negro slaves they encountered during their advance, and some 8,000 freed slaves joined the French.

The Mexican army fell steadily back until Consalus replaced General Vincent Collins with General Emiliano Calles. Calles brought reinforcements to the front, and defeated the French on 28 August at the Battle of Chapultepec, forcing their surrender. Calles then placed the French forces at Tampico under siege, while the Mexican Navy forced the French Navy to withdraw on 17 September. The French marines at Tampico finally surrendered on 29 September. Fanchon sued for peace on 3 October, and an armistice was declared on 10 October.

The Chapultepec Incident

After the French surrender at the Battle of Chapultepec, Consalus ordered the freed slaves arrested and put on trial for treason. Ullman argued that the slaves could not be tried for treason, since they were not considered Mexican citizens. The Chapultepec treason trials provoked protests from the governments of Great Britain, the Germanic Confederation, and Italy, and the Pope sent a special plea to Consalus asking for clemency.

In January 1915, Howard Washburne, the Governor of Southern Vandalia, demanded that the captured slaves be released, and the following month he called for the abolition of slavery in the U.S.M. Governor-General Albert Merriman apologized to Consalus, but Washburne's stand was a popular one in the Confederation of North America. Thirty-four members of the Grand Council signed a petition supporting the Washburne statement, and an organization was formed called the Friends of Black Mexico with Washburne at its head.

By December 1915 the tumult had died down somewhat, when Judge Homer Mattfield of the Mexico Tribunal, which was presiding over the trials, announced that a final verdict would be handed down on 5 January 1916. On the morning of 4 January, riots broke out in the Negro section of Chapultepec, and while the police and the Capital Guard were busy dealing with it, 2,000 young people stormed the Federal Prison and freed the slaves, at a cost of 1,166 dead and some 4,000 injured.

The next day, investigators at the Federal Prison reported that some of the prison guards had cooperated with the attackers, and that at least 200 of the 549 attackers who had died during the attack were North American citizens. Consalus ordered the Mexican Army on the alert and sent the Navy out of ports, while residents of Anglo and Hispano areas of the country began to arm against a feared slave rebellion and possible North American invasion.

Consalus and Merriman held a series of telephone conversations, and Merriman announced on 6 January that those North American citizens who had participated in the Chapultepec Incident had done so "without the knowledge of this government and certainly without its sanction. Measures will be taken at once to ensure that further incidents involving C.N.A. citizens in Chapultepec and other parts of the United States of Mexico will be prevented." Within the next two weeks, the passports of 10,970 North Americans then in Mexico were revoked, and their holders were told they must leave within three days. Eventually 232 of them were seized by the C.B.I. and charged with "actions injurious to the nation." 154 of them were found to be directly or indirectly involved in the Chapultepec Incident and were sentenced to prison.

The Slavery Dilemma

Before the Chapultepec Incident, slavery was not considered an important issue in the U.S.M. Reformers concentrated their attention on equal rights for Mexicanos and women, and Kramer Associates President Douglas Benedict did not consider manumission necessary for a stable nation. After the Incident, slavery became a national obsession. Every unfamiliar Negro was suspected of being a runaway, and there were constant fears of slave rebellions. Libertarian politicians known to favor manumission were hounded by their opponents, and in March Ullman was shot at while entering his home. By the summer of 1916 any Mexican Negro found in Anglo or Hispano neighborhoods ran a strong risk of being killed. Consalus was forced to institute a program of internal passports, and curfews were enforced in Tampico, Vera Cruz, and Mexico City.

Consalus established a number of commissions to investigate slavery in the U.S.M., and a series of reports on the subject were issued in 1916 and 1917. The best-known was the Holmes Report, authored by Theodore Holmes, a major Mexican scholar. Holmes proposed that Negro slaves be freed, but since he believed that Negroes could not live peacefully with the other races in Mexico, they should be allowed to emigrate, possibly to the C.N.A.

Consalus rejected Holmes' plan to allow the Negroes to emigrate. "One day," he said, "they may return to haunt us." However, he was unable to come up with an alternative. "If I retain the institution I will be pilloried. Should I ask for its end, I will be crushed."

General Calles' victory over the French in 1914 had made him the most popular man in Mexico, and in December 1919 Consalus met with him and offered to make him the U.M.P.'s presidential candidate in the upcoming elections. "There is no reason to hurry your reply, Emiliano. But if you are interested, it would be best that some of us know now." Calles insisted that he had no interest in politics. However, two months later, he met with Albert Ullman, and the two men talked at great length. At the Liberty Party convention in March, the delegates bypassed Ullman and drafted Calles, a maneuver that had been arranged behind the scenes by Ullman himself. The U.M.P. renominated Consalus.

During the campaign, Consalus pointed out that Calles had gone back on his word not to run for president, and that he had no political experience. Consalus and Calles held a vitavised candidates' debate on 29 March at which Calles was visibly ill at ease and performed poorly. Nevertheless, in the 1920 Mexican elections in April Calles defeated Consalus by 11,842,690 votes to 10,214,835, winning majorities in every state but Jefferson and California.

Sobel makes no mention of Consalus' life after his defeat in 1920.

Sobel's sources for the life and political career of Victoriano Consalus are Emiliano Calles' The People and the Nation (Mexico City, 1931), Edward McGraw's The Hundred Day War: An Analysis and History (Melbourne, 1950), Harold Walker's The Boil: Free Slaves in the Hundred Day War (New York, 1955), Charles Adkins' A History of the United Mexican Party (Mexico City, 1959), Jerome Krinz's Victoriano Consalus and the Politics of Race (New York, 1960), Phillip Daley's The Hundred Day War (New York, 1966), and Clyde Herman's The Gathering Storm: The End of U.S.M. Slavery (New York, 1967).

This was the Featured Article for 30 December 2012.

| Heads of State of the U.S.M. |

|---|

| Andrew Jackson • Miguel Huddleston • Pedro Hermión • Raphael Blaine • Hector Niles • Arthur Conroy • Omar Kinkaid • George Vining • Benito Hermión • Martin Cole • Anthony Flores • Victoriano Consalus • Emiliano Calles • Pedro Fuentes • Alvin Silva • Felix Garcia • Vincent Mercator • Raphael Dominguez |