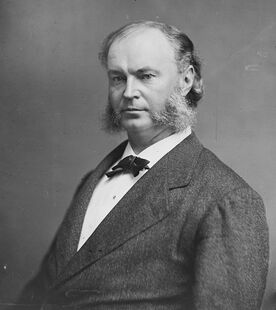

Thomas Rogers of Arizona.

Thomas Rogers was a member of the Liberty Party from Arizona. He served as Governor of Arizona until 1875, and in the Mexican Senate from 1875 until he fled the United States of Mexico in September 1881. He was the Libertarian candidate for President of the U.S.M. in 1875, finishing second in a three-way race against incumbent President Omar Kinkaid of the Continentalist Party and Senator Carlos Concepción of the breakaway Workers' Coalition.

1875 Election Campaign[]

As Governor of Arizona, Rogers had a strong record as a reformer, implementing mine-safety laws, and the U.S.M.'s first accident and unemployment compensation laws. Rogers was also a life-long opponent of slavery.

Rogers first came to national prominence at the Libertarian national convention in April 1875. Although Mexico del Norte Governor Henry Colbert, the party's 1869 nominee, was an early favorite, by the third day of the convention, Rogers and Senator Concepción of Chiapas had gained the support of the delegates.

Rogers spoke out against slavery, announcing, "If I become president, I shall destroy this evil, root and branch." He also pledged himself to "bring all Mexicans to full citizenship." Unlike Concepción, however, Rogers would not advocate attacks on the capitalist system itself, denoucing "those who would destroy, not create."

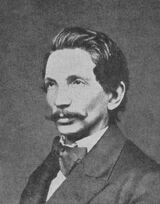

Senator Carlos Concepción.

Rogers gained the Libertarian nomination on the second ballot, winning the support of the party's Anglos, moderate Mexicanos, some Indians, and most of the Hispanos. Immediately afterwards, he made the customary appeal for party unity, but Concepción had already walked out of the convention. The day after Rogers' nomination, Concepción announced that he would form a new party called the Workers' Coalition, and would oppose both Kinkaid and Rogers at the polls.

While campaigning that summer, Rogers stressed the same issues he had dealt with as Governor of Arizona, outlining a program of social insurance and aid to education. He also pledged to amend the Constitution to abolish slavery, investigate big business (by which he clearly meant Kramer Associates, the country's largest corporation), and "redirect our effort toward making a better Mexico, for all Mexicans." Rogers criticized Concepción for "having lost faith in our people, and substituting force for reason." He also denounced "the plutocracy of the Constitutionalists, and the hypocrisy of a President who is on a leash, but does not know it, or does not care."

In the 1875 Mexican elections, Rogers finished first in the states of Chiapas, Durango, Arizona, and Mexico del Norte, and received 37% of the votes. However, Kinkaid's leads in the more populous states of Jefferson and California allowed him to win an outright majority of 52% of the votes. Concepción, coming in third with 11% of the votes, declared the Workers' Coalition dead, replaced by a revolutionary movement called the Moralistas dedicated to the overthrow of the Mexico City government.

Senate Minority Leader[]

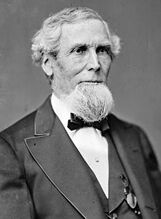

President Omar Kinkaid.

Within three months of the election, Senator Hiram Green of Arizona stepped down, and Rogers' successor, William Simmons, appointed him in Green's place. Rogers was elected Senate Minority Leader by the Libertarian caucus, and prepared to wage legislative war on Kinkaid. However, Kinkaid had been shaken by the divisiveness of the campaign, and by the growing strength of Concepción's Moralista movement. He also became aware of the extent to which he had been manipulated by K.A. As a result, beginning in 1876, Kinkaid began to embrace the reform agenda of his predecessor, Arthur Conroy.

Conroy was a close personal friend of Rogers, in spite of their being in opposing parties, and he was able to broker an understanding between the two. Although K.A. President Bernard Kramer opposed Kinkaid's reforms, a de facto alliance between the Libertarians and Kinkaid's supporters among the Continentalists allowed Rogers to pass the Thomas Railroad Reform Act, the Keefe-Wilkinson Social Insurance Bill, and the Fernandez Tax Reform Bill of 1878.

Sobel states that there was talk of Kinkaid naming Rogers his Secretary of State, and rumors that Kinkaid intended to support Rogers in the upcoming 1881 elections. Kinkaid may also have been planning to run himself for a third term, but such any such plans he had were ended on 7 December 1879, when he was killed by a thrown bomb during a parade.

The bomb thrower was never found, which led to uncertainty over who was responsible for Kinkaid's death. Rogers claimed that Concepción was responsible, while Concepción himself, through spokesmen, denied it and claimed to know for certain that Kramer and Benedict had been behind the assassination. Sobel states that Kramer privately believed that Rogers himself was behind Kinkaid's death.

Moralista Insurgency[]

George Vining of Jefferson.

Although Rogers was now a suspect in Kinkaid's death, he refused to withdraw from the balloting to choose a successor. The Senate went through several ballots before Rogers was willing to concede that he could not gain a majority of the votes. The Senate finally selected Senator George Vining of Jefferson to replace Kinkaid. Although Sobel initially indicates that Vining selected Rogers as his Secretary of State, it is clear that Rogers remained at the head of the Libertarian caucus in the Senate. It may be that Vining initially nominated Rogers for the office, but that Rogers' enemies, including Kramer, were able to prevent his confirmation.

In order to combat the growing Moralista movement, Vining created the Constabulary, an elite corps of police and soldiers operating in civilian clothes. He named Benito Hermión, the son of former President Pedro Hermión, as Commandant of the Constabulary.

In July 1881, at the Liberty Party's nominating convention, Rogers was again chosen as the party's presidential nominee. In his acceptance speech, he called Concepción "a cancer that would destroy our society, and bring to an end this noble experiment in republicanism." At the same time, Rogers denounced the power of Kramer Associates and Petroleum of Mexico, saying, "The large corporations of California and Jefferson control not only those states, but the rest of the nation as well. Large problems require large solutions. If elected, I promise to curb the influence of those elements in our society that operate against the common good."

Benito Hermión.

Eleven days after Rogers' nomination, the Workers' Coalition held its own convention in the Chipan capital of Palenque. The convention was raided by Constabulary agents on its opening day, and a firefight broke out between Constabulary agents and W.C. delegates. Twenty-three delegates were killed, including W.C. leader José Godoy, and the Massacre of Innocents at Palenque led to a full-scale uprising by the U.S.M.'s Mexicanos.

Vining called a special meeting of the Cabinet, to which he invited Rogers and other Libertarian senators. He and Rogers agreed to postpone the 1881 Mexican elections from 14 August to 21 September. In addition, Mexico was placed under martial law, Constabulary officers were given powers over the regular army, and Hermión was placed in charge of the campaign to end the Mexicano insurrection.

Flight and Exile[]

On the morning of 12 September, Vining was visited by a delegation of Libertarian senators who protested the abuses of the Constitution by Hermión's agents. Vining told them, "Have no fear for the Constitution. I have it here in the Palace, and will release it once peace returns to our land." However, any plans Vining was contemplating were cut short that afternoon, when he suffered a fatal heart attack.

The next day, for the second time in two years, the Senate met to choose a successor to a dead president. The task was complicated by the fact that the presidential election was only eight days away, and the Continentalist Party had no nominee. The Libertarians supported Rogers, while the Continentalists favored Secretary of State Marcos Ruíz. The Senate was deadlocked until Senator Frank Hill, acting on orders from Bernard Kramer, proposed that the Cabinet act as a collective executive until the elections. Under the pressure of the emergency, and possibly with financial encouragement from Kramer, the Senate agreed to Hill's proposal.

At the next Cabinet meeting, two days later, Hermión claimed to have proof that several important Libertarians were under the control of French revolutionaries, but that he could not reveal his evidence because two members of the Cabinet were themselves working for the French. He proposed that the election be postponed indefinitely, and the Cabinet voted seven to four to do so. Hermión then proposed the creation of the office of Chief of State to serve as national executive during the emergency, and this was also passed. The Cabinet then voted to make Hermión himself Chief of State.

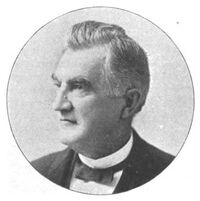

Fritz Carmody of Mexico del Norte.

The next day, Hermión appeared before the Senate to request confirmation of the Cabinet's decisions. The Libertarian caucus strongly objected, with Rogers denouncing Hermión as "a man of great ambition but little character." A vote on Hermión's request was postponed until the next day. However, that night, Constabulary agents arrested five Libertarian senators, including Rogers' chief lieutenant, Fritz Carmody of Mexico del Norte. Rogers himself was warned of the action and escaped from Mexico City, along with his family and those of imprisoned Senators Schuyler Stanley and Winthrop Sharp.

Rogers and his family fled to the Bahamas, where they remained for the rest of the Hermión dictatorship. Three years later, on 12 June 1884, Rogers gave an interview to a reporter for the London Times, in which he said, "We did much that was wrong and foolish, but at the time these actions seemed prudent and sensible. Our liberties were taken from us by stealth and over time, and not in a single day. And we helped those who had robbed us of our freedoms."

Sobel makes no further mention of Rogers after his 1884 interview.

Sources[]

Sobel's sources for the career of Thomas Rogers are the 29-30 April and 2-3 May 1875 issues of the Mexico City Journal; the 2-4 May 1875 issues of the Sangre Roja Voice; the 30 April 1875 and 5 July 1881 issues of the Mexico City Times; the 8 July 1884 issue of the London Times; Earl Watson's The Right Man: The Vining Administraion (Mexico City, 1943); Felix Lombardi's The Three-Cornered Hat: Conceptión, Kinkaid, Rogers, and the Election of 1875 (Mexico City, 1955); and Bernard Mix's The Night of the Caballeros: The Hermión Seizure (London, 1964).

This was the Featured Article for the week of 8 December 2013.