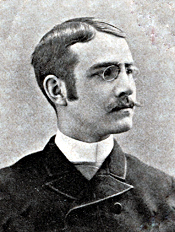

British novelist Burnet Mayfield.

The Moral Imperative was an ideology that appeared throughout Europe and North America in the 1890s. Its supporters believed that it was the "moral imperative" of the industrialized nations to bring the blessings of civilization to less advanced peoples. Although the movement began in Great Britain, it had adherents in every nation of Europe and the Americas.

Origins of the Moral Imperative[]

The Moral Imperative originated in a novel of the same name published in 1893 by the British writer Burnet Mayfield, in which the hero becomes a missionary in the Congo and leads the peoples of the region to Christianity and industrialization. The Moral Imperative found a wide readership in Britain, and an even more enthusiastic audience in the Confederation of North America. In Britain it was adopted by members of the Tory Party, as well as by Darwinian scientists, journalists, and poets.

The Neiderhofferist historian Martin Van Beeck claimed that the Moral Imperative "provided the rationale for modern imperialism, just as Protestantism offered heavenly justification for seventeenth century capitalism. There is something in Western man that requires him to have a mandate from God whenever he wants to enrich himself materially. If he wants it enough, the mandate will always come, in one way or another." Sobel claims that in spite of the assertions of Van Beeck, the Moral Imperative was never a mask for economic gain, since its most ardent supporters were the lower classes and professionals, while business generally fought the idea of mission, preferring trade and investment instead. Sobel does admit that those Europeans who plundered Africa and Asia around the turn of the twentieth century spoke of the need to "enlighten" those whose lands they conquered, just as the conquistadores had claimed in their period.

Advocates of the Moral Imperative[]

Thomas Kronmiller of Indiana.

In the C.N.A., the Moral Imperative's most famous advocate was Professor Henry Newton of Burgoyne University, who had previously published The North American Mission in 1882, which anticipated the movement's ideology and goals. The leading political advocate of the Moral Imperative was Thomas Kronmiller, a member of the Grand Council from Indiana, and the leader of the radical wing of the People's Coalition. Kronmiller privately spoke of a war with the United States of Mexico as a "great moral crusade" whose goals would be to "liberate the enslaved peoples of Guatemala and New Granada, return Hawaii to its former free state, and most importantly, rid the world of its last vestige of slavery."

In the U.S.M., William Randolph Hearst of the San Francisco Examiner was a leading advocate of the Moral Imperative, and the author of 1897's The Blood in Our Veins. Harry Doxey of the Jefferson Courier wrote on 5 May 1896 that the people of Guatemala and New Granada "have had their chances for greatness, and have failed due to a lack of the divine spark. Mexico possesses such inspiration, and therefore will carry Civilization southward." Benito Hermión himself justified the annexation of Hawaii by saying, "They will give us sugar, and we will give them Civilization. It is a fair trade." After the conquest of Siberia in 1899, Hermión said, "Under the Siberians the land lay fallow. We will make it bloom. All will benefit thereby. It is God's will as well as our own."

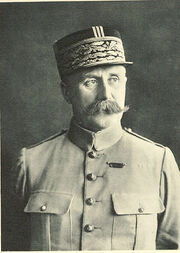

Marshal Henri Fanchon.

In France, the Moral Imperative inspired Marshal Henri Fanchon, who became head of a provisional government after a coup d'etat in 1909. Fanchon was a devoted expansionist who spoke of Joan of Arc, glory, and duty. "France has a mission," he said. "We cannot fail our blood and our history." In this way he was able to unite a nation that had been torn apart by civil war since the French Revolution of 1879.

Like Kronmiller of the C.N.A., Fanchon sought war with the U.S.M. as a way to realize his dreams of global dominance. However, unlike Kronmiller, Fanchon had the political power to pursue his war. After winning election in 1911 as President of France under a new constitution, Fanchon built up French military strength, then launched the Hundred Day War against the U.S.M. in 1914.

Sobel's sources for the Moral Imperative include Newton's The North American Mission (New York, 1882); Mayfield's The Moral Imperative (London, 1893); Hearst's The Blood in Our Veins (Mexico City, 1897); editor Franklin Nunn's The Moral Imperative (London, 1945); Van Beeck's A World Gone Mad and Its Cure (The Hague, 1945); Russell St. John's The Cutting Edge of Civilization: The Moral Imperative (New York, 1967); Henry Kurtz's The Moral Imperative: Its Origins and Development (New York, 1968); William Paca's When the World Went Mad: The Utopians of the 1890's (New York, 1968); and editor Benjamin Neely's The Moral Imperative (New York, 1970).

This was the Featured Article for the week of 2 June 2013.