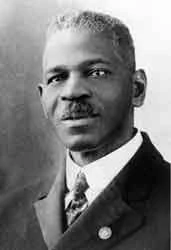

Howard Washburne of Southern Vandalia.

Howard Washburne (? - 1929) was the Governor of Southern Vandalia and the founder of Friends of Black Mexico and the League for Brotherhood.

Washburne was the Governor of Southern Vandalia and a potential candidate for Governor-General in 1914 at the time of the Hundred Day War between France and the United States of Mexico. At the end of the war in September 1914, the French left behind 8,000 Mexican Negro slaves who had deserted and joined their invading army. The slaves were arrested, charged with treason, and tried en masse by the Mexico Tribunal.

Early in 1915, Washburne called for the slaves to be released, and on 10 February he demanded that slavery be abolished in the U.S.M. "Our brothers are in chains, and their cries never leave our ears. We can no longer tolerate it. Either Mexico will end slavery, or we will do it for her." Governor-General Albert Merriman apologized to President Victoriano Consalus for Washburne's remarks, but millions of North Americans supported Washburne, including thirty-four members of the Grand Council. Within a week, Washburne had resigned as Governor of Southern Vandalia and founded Friends of Black Mexico, an organization dedicated to the abolition of Mexican slavery.

On 4 January 1916, the day before the Tribunal was due to deliver its verdict on the slaves, the Federal Prison in Chapultepec was stormed by two thousand F.B.M. members and the slaves set free. The Confederation Bureau of Investigation arrested 232 F.B.M. members and charged them with "actions injurious to the nation," eventually convicting and imprisoning 154. As a result of the C.B.I.'s actions, there were protest rallies across the C.N.A. Washburne spoke at the Burgoyne rally on 18 February, pledging himself to the "unceasing effort to bring freedom to our brothers in Mexico, to free not only the Negro, but the Mexicano and Indian as well." Washburne announced a boycott of all Kramer Associates products being sold in the C.N.A., and twenty-four-hour vigils outside U.S.M. consulates, and concluded, "We shall not rest until we reach the conscience of the Mexicans, and when we do, slavery and other evils of that benighted land will come to an end."

Although the vigils were sparsely attended, several turned violent as the protestors were attacked by racially-motivated counterdemonstrators in cities throughout the Northern Confederation, as well as in the Southern Confederation, Indiana, and Northern Vandalia. As passports and curfews were instituted in the U.S.M. and anti-black violence increased there, the vigils outside Mexican consulates became angrier, and the consulates in Michigan City and Flange, Manitoba were burned to the ground. Membership in the F.B.M. continued to grow, until by the spring of 1920 the organization had three million members, one million of them white. By then, Washburne was already changing the focus of his goals from the condition of Negroes in the U.S.M. to that of those in the C.N.A. In 1919, he stated, "What the Negro wants is the same kind of home, job, and life that his white brothers enjoy east of the Mississippi."

With the abolition of slavery in Mexico on 13 May 1920, the F.B.M. had achieved its objective. At a mass meeting the next day celebrating abolition, Washburne announced "the beginning of a new crusade, one to remake the face of our own land. Like the ending of slavery in Mexico, this too has been long overdue. The F.B.M. is dead, felled by its own success. Now the fight for democracy will be spearheaded by a new organization, the League for Brotherhood, which will welcome support from all men of good will, whatever their race or station in life. The fight for manumission in Mexico has lasted four years. This new struggle will take more than four times four years. We may not see its end, just as Moses did not enter the promised land. But the path is open. The way is clear. We shall prevail." (Sobel erroneously gives the date for this rally as 14 April 1920.)

Washburne intended to make the League for Brotherhood into a nationwide organization dedicated to ending racial discrimination in the C.N.A. However, as the League expanded to include reformers with different agendas, Washburne's own original agenda was lost. By the middle of 1921, the League had grown to seven millions members, the majority of them middle-class whites who rejected capitalism and industrialization. By then, the League had gained a new set of leaders, including Ivan Falls of the Agrarian Alliance, Fred Harcourt of the Workers' Army, Arnold Gelb of the Universities for Justice, the novelist Jeremy Slater, and Bryan Coleman, although Washburne remained the most popular. There was a movement within the Liberal Party to nominate Washburne for Governor-General in 1923, but he was not interested in political power. Instead, he used Biblical language to call for the moral regeneration of the C.N.A., and spoke of the need for brotherhood.

By 1922, the League was at the center of a growing mood of dissatisfaction with the status quo. The summer of 1922 saw major riots and demonstrations across the C.N.A., the worst since the 1880s. Finally, the cause of reform was taken up by locomobile magnate Owen Galloway, who announced his own Galloway Plan in a vitavised address on 25 December 1922. Galloway's proposal to subsidize emigration within and from the C.N.A. attracted the support of many League members, including Washburne, who said in March 1923, "We are in a time of diffusion, but good will prevails among men of honor."

Washburne left the League later that year, and was almost a forgotten man by the time of his death on 28 August 1929. His last words were, "I have been trampled to death by history."

Sobel's sources for the life of Howard Washburne are James Chester's Washburne of the C.N.A. (London, 1928) and Harold Walker's Black Lloyd: The Life of Howard Washburne (New York, 1970).

This was the Featured Article for the week of 9 December 2012.